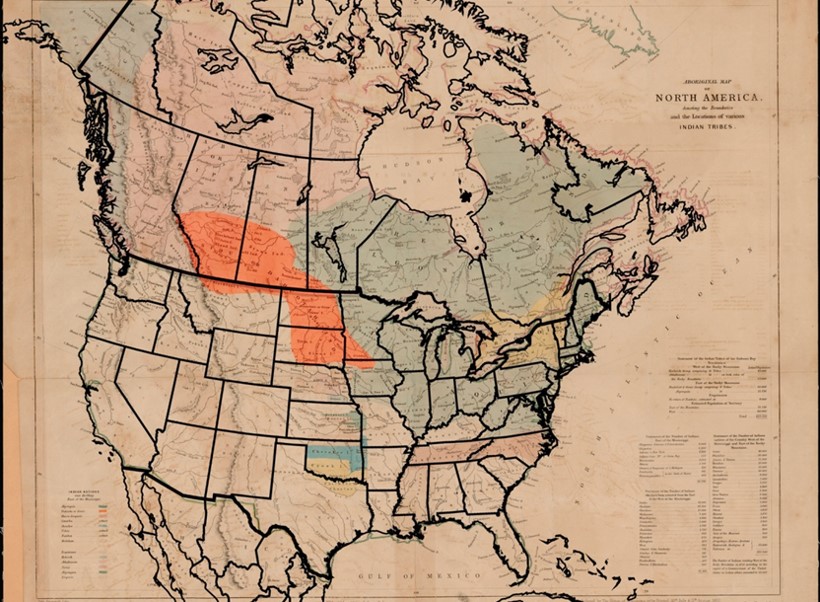

The Dakota Nation's traditional territories span large sections of contemporary United States and Canada, . The first European newcomers to arrive in Western North America were French explorers, fur traders, and missionaries in the mid-seventeenth century. New France’s Anishinaabe allies described their Dakota western enemies as na-towe-ssiwa, (translated to “people of an alien tribe”). As a result, the French referred to the Dakota variously as “Naduesiu,” “Nadoessi,” “Nadouessi,” “Nadouessioux,” which British and American fur traders later shortened to “Sioux.” However, the term “Sioux” should be avoided, as it was derived from a derogatory term. Instead, these nations use the names: Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota. The French envisioned the Dakota homeland as analogous to the Upper Mississippi River Valley. In reality, the Dakota controlled a much vaster territory that stretched from the Upper Mississippi River to the Middle Missouri River. The Dakota had three principal divisions – the Dakota to the east, the Nakota in the centre, and the Lakota to the west. In the east, there were four Dakota subdivisions of Mdewakanton, Sisseton, Wahpeton, Whapekute. The central Nakota subdivided between the Yankton and Yanktonai (“Little Yankton”). The Lakota subdivisions were more nebulous but divided themselves into smaller political units at the regional level, they are somethings known as the Teton or Teton Sioux. The Dakota recognized these subdivisions as seven distinct oyate (a word best translated as “people”) and referred to themselves collectively as the Seven Council Fires (Oceti Sakowin). The Mdewakanton, Sisseton, Wahpeton, Whapekute, Yankton, Yanktonai, and Lakota were ancestral political units of the Seven Council Fires (Oceti Sakowin). Even though different in many respects, all three groups were politically united and referred to themselves a collective Dakota, Nakota, and Lakota alliance.

Starting in the eighteenth century more and more Sioux bands migrated deeper into the west, following herds of buffalo onto the northern Great Plains. The Nakota and Lakota began to acquire horses in the first decades of the eighteenth century. In total, the Seven Council Fires encompassed a population of 24,000 and possessed an unparalleled military capability that exceeded the power and reach of the British or French Empire in North America. In the east, however, the Dakota peoples of Upper Mississippi River Valley – the Mdewakanton, Sisseton, Wahpeton, Whapekute – became specialists in the fur trade and diplomacy. The Sioux effectively controlled access to their prairie hunting grounds on the Northern Great Plains from the east, and thus policed the flow of people and goods between the Atlantic World and the heart of North America. The fur trade shifted some economic conditions and altered some of the everyday aspects of the Dakota lifestyle – the Dakota incorporated manufactured European trade goods, such as firearms, iron knives and hatchets, coarse woollen cloth, wool blankets, cooking utensils, beads, and needles – but they did not allow to them to undermine or alter their culture, beliefs, and traditions. However, as time went on, the fur trade did have an adverse effect on the Dakota, who had become more reliant on the fur trade for wellbeing. Moreover, the fur trade also brought unintended side effect of the introduction of virgin soil disease epidemics – smallpox, influenza, measles, and whooping cough – that devastated Dakota populations.

Following the British Conquest of French Canada, the Dakota became stalwart allies of Great Britain and formalized a long-standing relationship with the British through wampum ceremonies and the signing of a treaty in 1787. The Dakota honoured this treaty by lending military support to the British in their fight against the American rebels in 1776 and again in the War of 1812. For their contributions to the war, the Dakota received medals, flags, and promises that the Crown would protect their territory and autonomy. When Great Britain and the United States signed the Treaty of Ghent in 1814 to bring an end to the war, the British promise to protect the traditional homeland was ignored. The Dakota then found themselves sharing their territory with their American enemies. The Dakota eventually negotiated treaties with the United States, but suffered years of injustice, systematic treaty violations, and forced starvation. Dissatisfied, the Dakota rebelled against the American government. Thirty-eight Dakota men were hanged as punishment – the largest mass execution in American history. Escaping American violence and discrimination, hundreds of Dakota crossed the 49th parallel seeking the opportunity for peaceful co-existence amongst their British allies. A decade later, a few Lakota, including Sitting Bull, also moved into southern Saskatchewan following the Great Sioux War of 1876.

In Saskatchewan, Standing Buffalo, Wahpeton, and Whitecap First Nations are descendants of the Oceti Sakowin. In the nineteenth century, the Crown had failed to recognize their former allies and instead mislabeled them “American Indians.” As a result, the Dakota did not get to participate in the Numbered Treaties between the Canadian Government and First Nations from 1871 to 1921. Therefore, Dakota whose homelands Saskatchewan and Manitoba overlap, are still pursuing the federal government for proper recognition and self-government.

Resources:

- Wahpeton Dakota Nation. Community History Report. 2012. WDN-community-history-report_optimised.pdf (sqspcdn.com)

- Whitecap Dakota First Nation. Our Community History. History - Whitecap Dakota First Nation

- Standing Buffalo Dakota First Nation - Indigenous Saskatchewan Encyclopedia | University of Saskatchewan (usask.ca)

- Dakota / Lakota - Indigenous Saskatchewan Encyclopedia | University of Saskatchewan (usask.ca)

- Gary Clayton Anderson, Kinsmen of Another Kind: Dakota-White Relations in the Upper Mississippi Valley, 1650-1862 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984).

- Peter Douglas Elias, The Dakota in Western Canada: Lessons in Survival (Winnipeg: The University of Manitoba Press, 1988).

- Michael Witgen, An Infinity of Nations: How the Native New World Shaped Early North America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012).