In the 1700s, the Métis formed as a distinct Indigenous people and culture, with identifable homelands, language (Michif), kinship networks, religion, social and legal customs, among other unique traditions. This ethnogenesis stemmed from marital unions between French-Canadian fur traders and Indigenous women, such as the Cree and Ojibwe in "Rupert’s Land" (Hudson Bay Watershed). Following the 1760 British Conquest of Canada, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and the rival North West Company (NWC) expanded fur trade networks throughout the Hudson Bay Watershed. While some HBC and NWC officials initially discouraged “country marriages,” sometimes called marriages à la façon du pays or “according to the custom of the country,” they soon realized that marriage and kinship were mutually beneficial in establishing trading alliances and relationships with Indigenous peoples.

Following the termination of contractual employment, many French-Canadian voyageurs chose to remain with their Indigenous wives in Rupert’s Land and to subsist as independent traders, trappers, and provisioners. These men, known known as gens libres, ‘freemen,’ and their Indigenous wives are the founders of a distinctive Métis identity in the Red River Valley. Consequently, their descendants formed a distinct culture, collective consciousness, and nationhood in the Northwest.

An important feature of Métis culture was the emergence of a distinct composite language – Michif (or Mitchif), which was based primarily on Plains Cree and Canadian French with a distinctive Saulteaux or Ojibwe element. The Métis blended European and Indigenous traditions to create a unique and rich culture. In traditional music and dance, Métis fiddling and jigging combine European and Indigenous influences. Métis art also reflects their dual heritage, adopting both Indigenous beading practices and popular European floral designs. Lastly, Métis gastronomy also reflects European and Indigenous hybridity with specialities of bannock, pemmican, tourtières (meat pies), pea soup, and wild rice.

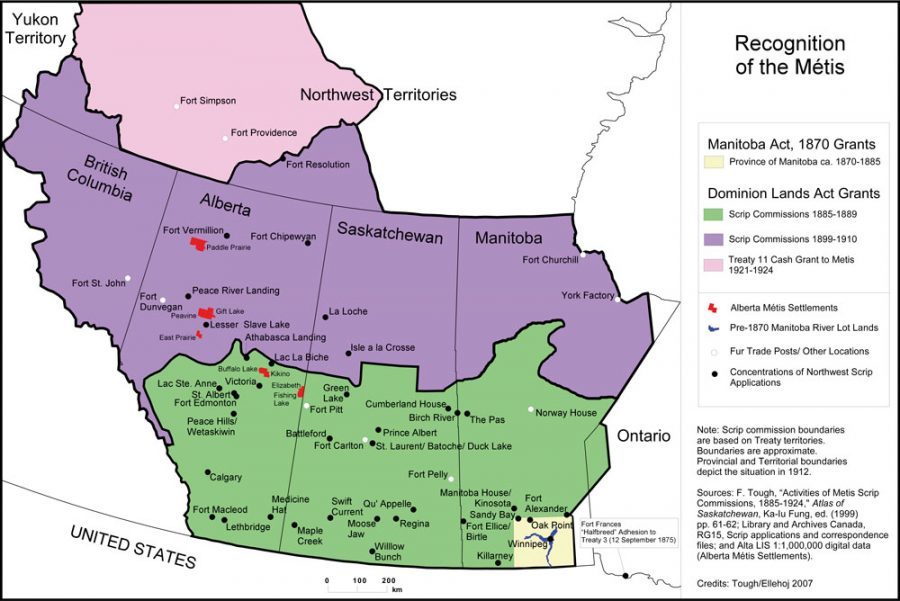

“Recognition of the Métis” map from John Weinstein’s book Quiet Revolution West: The Rebirth of Métis Nationalism.

But as recent scholarship by Chris Andersen has argued, Métis should not be reduced to the idea of “mixedness.” Rather, Anderson argues that to be Métis is to be connected to and belong to one of the historical Métis communities of the Prairies who organized themselves as a society with the ability to negotiate relations with others. The concept of Métis nationhood can be traced to the settlements at Pembina and the Forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers. Unlike some other ‘half-breeds’ that arose from the HBC’s fur trade posts, who aspired to assimilate into the British-Protestant world of their usually higher-ranked fur trader fathers, the Métis progeny that arose from the NWC’s initial fur trade marriage alliances developed a tradition of resistance to the political and economic control exercised by Euro-Canadian fur trade companies. As a people independent from other European and Indigenous societies, the Métis pursued trade and political alliances with the Plains Ojibwe, Plains Cree, Assiniboine, and Blackfoot and often acted as intermediaries between them and Euro-Americans and Euro-Canadians. The Métis frequently quarrelled with the Dakota and Lakota for control of bison-rich hunting territories between the South Saskatchewan River and Missouri River. The Métis rivalry with the Dakota/Lakota for control of bison-hunting territories culminated in the Battle of Grand Coteau in North Dakota in 1851, where the Métis emerged victorious.

By 1810, the Métis provisioned NWC trading posts and fur brigades with Pemmican, which was made by pounding dried bison meat with berries and pouring melted fat over the mixture, and was a dense, high-protein and high-energy food that could be stored and shipped with ease to provision voyageurs in the fur trade travelling in the prairie regions where regular game could be scarce (2 lbs of pemmican provided around 8,000 calories). As NWC supply lines lengthened to the Athabasca Basin and the Columbia Plateau, the Red River heartland became crucial to the Montréal-based traders as a provisioning centre. The Red River Colony (founded jointly by Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk and the HBC in 1812) issued the Pemmican Proclamation in 1814, which forbade the export of pemmican and other provisions from the Red River Colony. The Pemmican Proclamation (as well as a ban on hunting bison from horseback) angered many Métis families, who saw the decrees as direct economic sanctions against them because they made their living by provisioning the NWC forts. Under the leadership of Cuthbert Grant, the Métis defended their economic and political right to land and resources at the Battle of La Grenouillère (a location known to the English as Seven Oaks) in 1816, where Red River Colony Governor Robert Semple was killed.

Photograph of Adolphus Ross and William Bird. 1910-1929. S-B513, Christina Bateman Fonds. Saskatchewan Archives

Board. Our Legacy.

In 1869, the HBC began negotiations with the British and Canadian governments for the transfer of Rupert’s Land, without consultation with its Indigenous and Métis inhabitants. The arrival of unauthorized Canadian surveyors and speculators from Ontario set into motion an organized Métis resistance under Louis Riel. While the Métis were concerned about their land, they were also worried that they would lose their language, religion, and culture. Although the 1869-70 Métis uprising in the Red River Colony had led to the creation of the Province of Manitoba and guaranteed that Métis land titles were recognized by the federal government, subsequent mismanagement resulted in disenfranchisement of many Métis families, whose lands were appropriated by newly arriving settlers from Ontario and Québec. Of the approximately 10,000 persons of mixed descent in Manitoba in 1870, two-thirds or more are estimated to have departed the Red River Valley in the following few years, with most headed west to the existing Métis settlements at St. Laurent, Duck Lake, Batoche, Lac Ste. Anne, St. Albert, and Lac La Biche.

Common earlier historical terms for the Métis include bois-brûlé, gens libres, ‘freemen,’ chicot, michif, Otipemisiwak, half-breeds, etc. Several of the terms coined by Europeans are now considered offensive.

Resources:

- Andersen, Chris. “Métis”: Race, Recognition, and the Struggle for Indigenous Peoplehood, Vancouver: UBC Press 2015.

- Macdougall, Brenda. One of the Family: Métis Culture in Nineteenth-Century Northwestern Saskatchewan. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2010.

- Adams, Howard. Prison of Grass: Canada From a Native Point of View. Saskatoon: Fifth House, 1989.

- Campbell, Maria. Halfbreed. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1973.

- Lischke, Ute and David T. McNab. The Long Journey of a Forgotten People: Métis Identities & Family Histories. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2007.

- Métis Communities - Indigenous Saskatchewan Encyclopedia | University of Saskatchewan (usask.ca)

- Métis Culture and Language - Indigenous Saskatchewan Encyclopedia | University of Saskatchewan (usask.ca)

- Métis Education - Indigenous Saskatchewan Encyclopedia | University of Saskatchewan (usask.ca)

- Métis Farms - Indigenous Saskatchewan Encyclopedia | University of Saskatchewan (usask.ca)

- Métis History - Indigenous Saskatchewan Encyclopedia | University of Saskatchewan (usask.ca)

- Métis Nation–Saskatchewan - Indigenous Saskatchewan Encyclopedia | University of Saskatchewan (usask.ca)

- Métis Women - Indigenous Saskatchewan Encyclopedia | University of Saskatchewan (usask.ca)

- Métis and Non-status Indian Legal Issues - Indigenous Saskatchewan Encyclopedia | University of Saskatchewan (usask.ca)