“Lots of changes in fifty years of trapping,” declared James Ratt in 1983. In fact, he added, it was “a way of life now almost gone.” James Ratt’s story of life on the trapline is a simple but profound documentation of the changing nature of northern life, seen from the eyes of the late twentieth century. His account of traditional trapline life, from the lengthy canoe journey to and from his family’s trapline, to the use of dog teams and bush routes that were ‘like a highway’ from so much traffic, and a memory of settlements and gardens long lost to time and the growing urbanization of Saskatchewan’s north strike a chord not often heard by those who study the fur trade.

Fur trade history is dominated by the economic and social history of the major industrial players – the Hudson’s Bay Company, the smaller Montreal trading firms, and others – but rarely do we hear about the life of the ‘suppliers’ on the trapline. It is an interesting story, the invisible backbone of the mighty fur trade empire that drove much of Canada’s development well into the 19th century, and in the northern boreal forest, well into the 20th. The seasonal nature of trapping, the kind of furs taken, the mechanics of setting up and running a trapline, and the connection between trapping, hunting, and other resource extraction activities will form the skeleton of this essay. Mechanization and transportation, the industrialization of the fur trade, changes in staple economics and Aboriginal society are key parts of this story. Trapping is not an isolated activity. It lies within a network of environmental, physical, social, political and economic pressures that constantly hover over the question: is trapping merely an economic activity, or is trapping a particular way of life?" (Massie, Merle, "Trapping and Trapline Life," in Our Legacy Essays, 143-144).

The implementation of provincial and federal game laws in the early 20th century like the Fur Conservation Act, Fur Conservation Board and Fur Blocks, and Fish Marketing Service were viewed as a method to moderate and protect game levels in the province. Governments saw game populations depleting and rationalized that First Nations and Métis' supposed mismanagement of game was responsible, along with illegal or overhunting from Settlers. New access restrictions and the reorganization of hunting, fishing, and trapping grounds interrupted the livelihoods of Indigenous peoples in the north, and for those who traveled to hunting and trapping grounds annually or periodically from Southern regions. Once the Northern Conservation Board Act was implemented in 1939, Indigenous people who were living outside of Northern communities had to apply to the Board for special licenses to obtain trapping, fishing, and hunting privileges at their discretion. Prior to changing the ways Indigenous Peoples accessed resources and traditional land-bases.

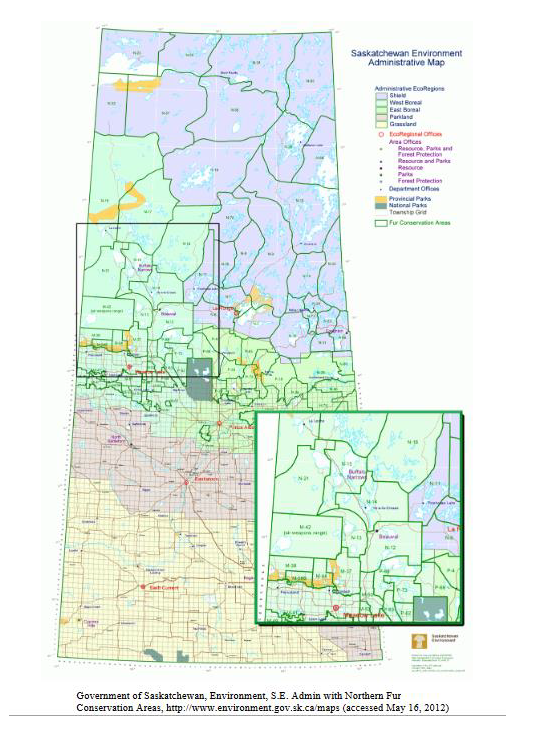

The Fur Conservation Agreement was passed in 1944; the ten year agreement, jointly funded by the provincial and federal governments, allowed the province to create a Fur Advisory Committee that would advise the government on matters of trapping conservation above the fifty-third parallel, which was divided into 39 ‘fur blocks.’

These regions were allotted to five-member trapper councils who were responsible for overseeing the conservation endeavors. Trapping was restricted to those who had lived in the north for at least a year (to protect northern trappers from seasonal trappers from the south) and who had no other major source of income outside of trapping.

Rules stipulated individuals could not trap outside of a certain area (the block or trapline) that was preapproved by the board. In doing so, this locked mainly Indigenous Northern trappers to a parcel of land. First Nations and Métis people who lived below the fifty-third parallel and traveled periodically to trap or hunt were incidentally excluded from the Fur Conservation Agreement, meaning that their access was denied altogether. While this measure was designed to stabilize the population of fur bearing animals, it became another controlling measure rallied predominantly against First Nations and Métis who practiced subsistence trapping, hunting, and fishing.

For Indigenous people who had established traplines, in many cases for generations, the new game laws created legal barriers to access, maintain, and harvest traplines that fell outside of their designated Fur block. Unconcerned with push back from Indigenous residents, the provincial government viewed the reorganization of Traplines as a minor issue. But, to the trappers and families it affected, the loss of income, food, and resources could be disastrous in both the short- and long-term. The reorganization of via fur blocks inhibited access to land-bases, long-time established traplines, posed an impediment in the transmission of intergenerational knowledge intrinsic to trapping and hunting, and the culturally important areas which they had been stewards of for centuries. Families relied on multiple traplines in pre-determined areas that were recognized amongst community members, sometimes 100s of kilometres away from home. Fur Blocks incited anger and resistance from Indigenous trappers because they threatened their livelihoods, cultures, and Treaty Rights.

New Game Laws incited resistance from Indigenous trappers who, in some cases, continued to maintain and use their existing and traditional traplines even if new conservation laws prohibited them. Not only was it an economic necessity for some trappers and their families to continue maintaining all their traplines, it was also a form of asserting agency and resistance to the settler colonial government. The punishment for non-state-sanctioned trapping and hunting could be fines, further restrictions, or jail sentences. Government officials and settlers viewed Indigenous trappers who ignored new regulations as criminals who were breaking the law. Indigenous agency became associated to behaviours that settler colonists viewed as criminal, especially when they themselves did not understand why First Nations and Métis were unwilling to “follow the rules” (assimilate) or give up their Treaty and Aboriginal rights.

A common theme in the implementation of Aboriginal policy was that if Indigenous peoples did not assimilate in the ways the government wanted, then they would not receive economic or social support (social welfare and government services). This is one way in which settler colonialism established inequity. Being that some Indigenous parents, families, and communities were rightfully unwilling to separate from their children or give up their traplines (where children were taken to learn and help), the government rationalized that welfare could be withheld. Gwen Beck, who was instrumental in applying the Family Allowance in La Ronge, recalls:

“I don't know exactly whether it was correct or not, but gradually the Family Allowance was the biggest drawing card for keeping families in [settlements]. But it did split up [the families]... the women had to stay behind or they had to find homes. We talked about building a hostel -- which we never ever got to -- to take the children so the children could stay. We went through all these phases but, you know, I think it finally ended up that more people stayed home and sent their children in school… Money- wise, money again was a big thing, the Family Allowance meant quite a lot to get, and most of them had good-sized families, you see. So it meant they stayed, and trapping became less and less, really. Even today they cannot support themselves by trapping, no matter how good a trapper they are, so you understand...” Beck, Gwen. Interview by Murray Dobbin. Transcript. July 20, 1976. Virtual Museum of Métis History and Culture. Gabriel Dumont Institute. Pp. 12.

La Ronge Resident Robert Dalby offered his view on the Family Allowance:

“Yeah, it started manifesting itself at that time and several reasons. It wasn't just economics. It was the growing population for one thing. It was beginning to grow because of health services and things. And I remember very distinctly the old business even with the treaty Indians, the treaty agent would threaten to cut off family allowance if the kids didn't go to school. So parents were compelled to stay in the settlements. At least the mother was compelled to stay in the settlement so that the kids went to school. And I know of several families, people I've known for twenty-five, twenty-eight years, who faced this situation. They could no longer go out to the trapline as a family group. The kids had to stay in school and these people around here, these bush people around here, have always respected the law. They haven't liked it necessarily, but they've respected it. And so if someone threatened to cut off the family allowance and threatened them with dire punishment, most of them went along with it and believed it, you know”. Dalby, Robert. Interview by Murray Dobbin. Transcript. June 18, 1976. Virtual Museum of Métis History and Culture. Gabriel Dumont Institute. Pp. 2.

The erosion of land and game rights, such as that through the Fur Blocks, have had cumulative effects. Oral testaments in books, interviews, and even the news from First Nations and Métis residents in the North describe that over time, disconnection from the land has impacted cultural knowledge, inability to access traditional territories and resources, unnecessary food scarcity, housing and employment insecurity, experiences of poverty, and deteriorated physical, mental, spiritual, and emotional health.

Currently, reconnection with land-bases and ancestral knowledge is underway by many Indigenous peoples, organizations, programs, and Nations to remediate the harms of settler colonialism and its intentional removal and isolation of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands and Canadian society (accomplished through marginal reserves). However, is it also important to remember that Indigenous peoples have always found ways to work around or within the structures of settler colonialism, maintaining their distinct cultures, traditions, nations, knowledge, and kinship despite the Canadian Government's genocidal measures. Since the retraction of Canada’s most aggressive genocidal policies following the closure of Residential Schools in the 1990s, there are fewer barriers in place that inhibit reconnection, revitalization, and cultural activities (like the Sun Dance and Potlatch) are no longer criminalized.

Sources:

- CCF Social Programming and Erosion of Traditional Lifeways in Northern Saskatchewan | Gladue Rights Research Database (usask.ca)

- “James Ratt: Lots of changes in 50 years of trapping.” Denosa, summer 1983. Northern Saskatchewan Archives, Pahkisimon Nuye?áh Library System

- Barron, F. L. Walking in Indian Moccasins the Native Policies of Tommy Douglas and the CCF. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997. 146.

- Beck, Gwen. Interview by Murray Dobbin. Transcript. July 20, 1976. Virtual Museum of Métis History and Culture. Gabriel Dumont Institute. http://www.Métismuseum.ca/resource.php/01180

- Dalby, Robert. Interview by Murray Dobbin. Transcript. June 18, 1976. Virtual Museum of Métis History and Culture. Gabriel Dumont Institute. 1-4. http://www.Métismuseum.ca/resource.php/01164

- Dayal, Pratyush. “Stumped.” CBC News Features. July 10, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/newsinteractives/features/stumped

- Massie, Merle. "Trapping and Trapline Life," in ka-ki-pe-isi-nakatamakawiyahk. Our Legacy: Essays. Saskatoon: University of Saskatchewan, 2008. 143-162.

- Quiring, David M. CCF Colonialism in Northern Saskatchewan. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2004. 104.

- Raymond, Deanna., and University of Saskatchewan, College of Graduate Studies Research. The Métis Work Ethic and the Impacts of CCF Policy on the Northwestern Saskatchewan Trapping Economy, 1930-1960, 2013. 58-60.

- Saskatchewan Archives Board. R-907.2, v. II, f. 12, "J.J Wheaton, Northern Administrator," J.L Phelps to Wheaton, 9 January 1948.