Indigenous women were especially affected by the gender rules and roles imposed by European colonialism. Colonial interests in the North-West sought to prevent the mingling of European and Aboriginal people by erasing successful past intimate relations, by presenting Indigenous women as a threat, and by encouraging the immigration of white women. British assumptions about the moral superiority of their version of marriage regarding the protection and empowerment of women, for example, was one way that it legitimized its rule over others. In the same way, a strictly monogamous legal conception of marriage was part of the Canadian national agenda, particularly in the west where other legal frameworks of marriage pre-existed and co-existed with the colonial norm. To preserve the purity of marriage it demanded no deviations, no divorce, and no remarriage.

Canadian law was not only biased against women, it was also a direct challenge to much more flexible Indigenous laws concerning marriage and was used to interfere in the lives of First Nations and Métis people. It served as a tool of racial segregation, keeping white and Indigenous people apart. It was also used to justify the surveillance and policing of the sexuality of Indigenous women, supervising them to see that they conformed to the Canadian purity laws and ideologies. Residential schools were complicit in this system – they sought to remake Indigenous women to fit European domestic and marital expectations. Scholars have noted that gender along with race were the sharp edge of colonial policy, politics, and programs designed to transform these social realities and replace them with a proper form of “civilization.”

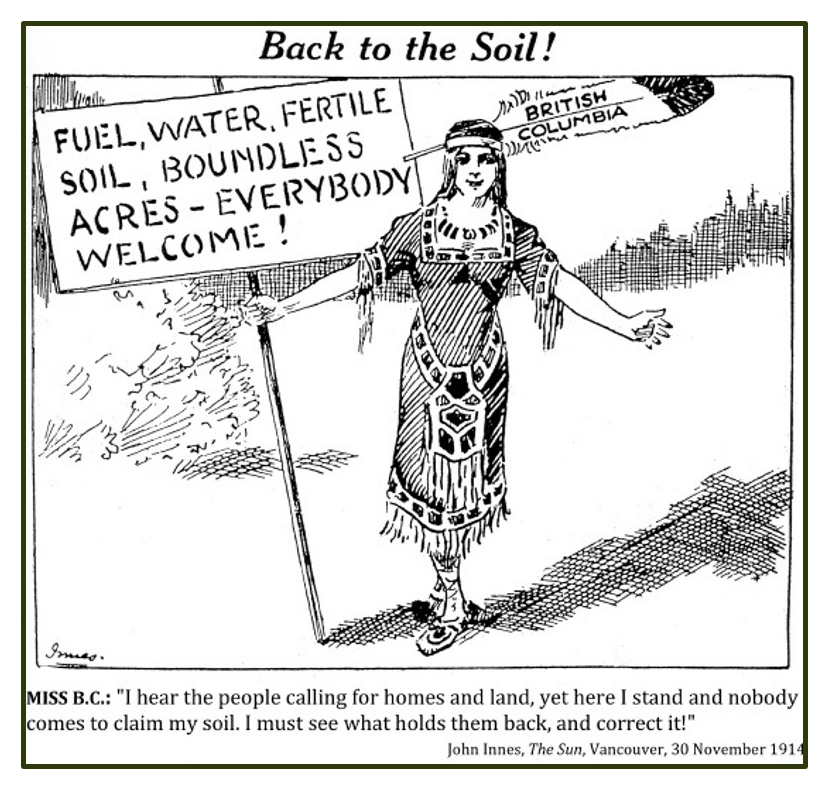

Images like “Miss B.C.” reinforced the colonial belief that Indigenous lands, and specifically Indigenous women and girls, were free to be taken by settler colonists.

Others have posited that attention to Indigenous women's labour after WWII provides insight into coercive federal Indian policies which continue to affect Indigenous peoples lives in Canada, contributing to land dispossesion and poor economic situations that many experience as a result of colonialism. For example, the instruction Indigenous girls received in residential schools directed them towards the lowest paid sectors in wage labour as domestic servants. This racist and gendered approach to labour instruction was scheduled as supervised cleaning and food preparation in the residential schools, and similar labour in the homes of government and church staff. These programs directed Indigenous women to jobs like private homes, hotels, tourist resorts, hospice, and care-homes - racism was and remains a systemic barrier to employment. Government programs that trained women for the workforce were informed by prejudices against Indigenous women and placed them in jobs where they were subordinated to men and paid unfairly.

The Gradual Enfranchisement Act 1869 replaced traditional and matriarchal forms of governance with the Indian Act, modelled after colonial gendered and sexual norms. Of particular importance to the government was expediting civilization and management of Indigenous lands. In order to accomplish these goals government defined 'Indian' identity based on registration entitlement and blood quantum. As such, early legislation targeted First Nations men while excluding women. A First Nations woman who married a man without Indian status was disenfranchised and not entitled to live on reserve. Her children were also excluded, measures which were aligned with Canada’s civilization, segregation and racial purity goals. In the Gradual Enfranchisement Act 1869, s. 6 introduced the loss of status clause which was used against First Nations women; and in cases where parents split, children were required to remain with the father’s band. The Gradual Enfranchisement Act 1869 also restricted the transfer of property to a First Nations woman, with inheritances passed to the children. The Indian Act 1876 continued the 1869 Loss of Status provisions with respect to First Nations women but at the same time provided for the acquisition of Indian status by white women who married a status-carrying man. Indian Act amendments also withheld annuity payments (Treaty moneys) if a childless First Nations woman lived with another man. In 1879, the Indian Act was amended to include clauses specific to First Nations women and prostitution.

The long-term colonial 'civilizing' mission outlined in the Indian Act envisioned the acquisition of private property and citizenship through Certificates of Possession (a.k.a Location Tickets), which allotted land holdings (plots) to individuals. In 1999 the First Nation Land Management Act was passed by Parliament. Fourteen First Nations across Canada were signatories of the Agreement with an opt-in opportunity for other First Nations. Once a First Nation opts into the FNLMA, those sections of the Indian Act pertaining to land holdings no longer apply. Instead, a community consultation process determines the content of a requisite land code and other provisions which fall under the Land Management regime. Land Codes are approved by INAC.

- Values of Gender Equality in Indigenous Societies

-

In partnership with the Kizhaay Anishinaabe Niin program and the Ontario Federation of Indian Friendship Centres, Kim Anderson, Robert Innes, and John Swift conducted 12 interviews with Indigenous Elders from across Canada, asking the questions: “What roles and responsibilities did Indigenous men have in the past? What happened to our men’s identities and masculinities as a result of colonization? Where are we at today? What do our men need to move forward in terms of being healthy Indigenous males?”[1]

“Several of the Elders spoke about the need for balance and respect between different genders and age groups in land-based communities of the past, stressing that good relations were critical to the survival of the people. Ted Quinney (Cree, Alberta) emphasized that patriarchy brought in ‘a whole hierarchy system,’ adding that ‘it was their failure to understand equality.’ He commented that in land-based societies ‘no one is supposed to put themselves above the collective whole, because the moment you do that, you put yourself and the collective in peril.’ Albert McLeod (Cree, Manitoba) talked about how homophobia was introduced as part of Euro-Western gender relations. He made reference to scholarship in this area, (e.g., Jacobs, Wesley, & Lang, 1997) stating that ‘there is evidence that two-spirit people were integrated in and integral to [our] societies.’”[2]

“Whereas men and women held distinct roles and responsibilities in traditional societies, the Elders noted that gendered roles and responsibilities did not involve the male dominance associated with patriarchal gender regimes. Ray Peter (Quw’utsun, B.C.) remarked, ‘[Europeans] came in and looked at women as just chattel … [A European women’s] job was to stay home, keep the house clean, keep the clothes clean, cook and bear children.’ He asserted that ‘our people [were] not that way. They were never that way. And so that’s one of the things that was broken.’

Gendered roles associated with labour in land-based communities were determined by practicality; typically men hunted large game while women managed the resources of the family and community. Yet unlike patriarchal gendered roles associated with labour, one role was not considered more valuable than the other, and there was a fluidity and flexibility that came from a necessity of survival […] Balance and respect for the different roles people played was key to fostering the health and well-being of family and community.”[3]

Footnotes:[1] Kim Anderson, Robert Alexander Innes, and John Swift, "Indigenous Masculinities: Carrying the Bones of the Ancestors," In Canadian Men and Masculinities: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives., Eds. Christopher J. Greig and Wayne J. Martino, (Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press Inc., 2012), 267.

[2] Anderson, Innes, and Swift, "Indigenous Masculinities: Carrying the Bones of the Ancestors," 268-269.

[3] Anderson, Innes, and Swift, "Indigenous Masculinities: Carrying the Bones of the Ancestors," 269. [references omitted]

Resources:

- Kim Anderson, Robert Alexander Innes, and John Swift, "Indigenous Masculinities: Carrying the Bones of the Ancestors," In Canadian Men and Masculinities: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives., Eds. Christopher J. Greig and Wayne J. Martino, (Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press Inc., 2012).

- Carter, Sarah. Capturing Women: The Manipulation of Cultural Imagery in Canada's Prairie West. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1997.

- Carter, Sarah. The Importance of Being Monogamous: Marriage and Nation Building in Western Canada to 1915. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2008.

- Cornet, Wendy and Allison Lendor. Discussion Paper: Matrimonial Real Property on Reserve. Cornet Consulting & Mediation, November 28, 2002.

- States of Emergency: Confronting the Erasure of Indigenous Women and Two-spirited People in HIV Movements. | Gladue Rights Research Database (usask.ca)

- Sexual Exploitation and Trafficking of Indigenous Women and Girls | Gladue Rights Research Database (usask.ca)

- Non-status Indians - Indigenous Saskatchewan Encyclopedia | University of Saskatchewan (usask.ca)

- McCallum, Mary Jane. Indigenous Women, Work, and History, 1940-1980. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2014.

- Perry, Adele. On the Edge of Empire: Gender, Race, and the Making of British Columbia, 1849-1871. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001.

- Allison Hargreaves. Violence Against Indigenous Women: Literature, Activism, Resistance. Waterloo: Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2017.