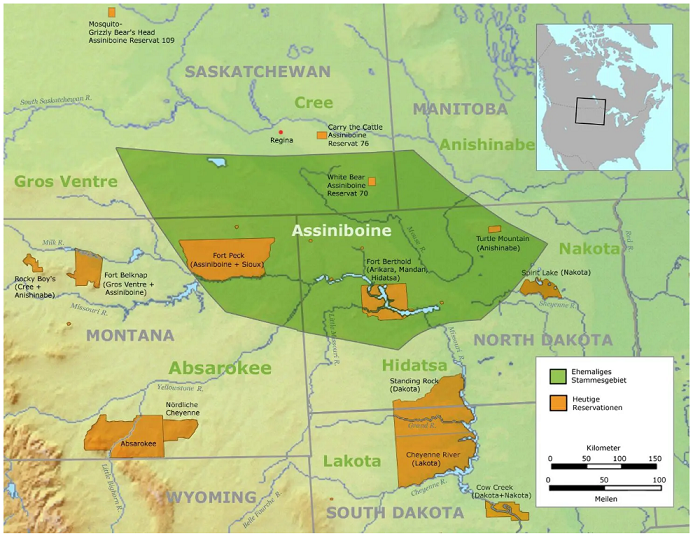

The Nakota / Nakoda / Nakoda Oyadebi (also known by the exonym Assiniboine) are a Plains Indigenous people whose territory spans across the contemporary Canada / United States border. Historically, the Nakota occupied Woodland and Aspen Parkland territory ranging between the Qu'Appelle Valley and Lake of the Woods. They are known as the “Nakota” or “Nakoda,” however the Ojibwe had introduced them to French traders as “asinii-bwaan” (stone Sioux), and thus "Assiniboine" was integrated into English and French vernaculars. As a result, the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North-West Company often referred to the Nakota as “Stone Indians,” “Stony Sioux,” or “Stonies.” The Nakota speak a Siouan language and were originally part of the Oceti Sakowin (Sioux Confederacy). By the time French and English observers arrived in the Hudson Bay Watershed in the early seventeenth century, the Nakota had broken away from the Oceti Sakowin and joined their Woodland Cree neighbours in a military and trade alliance, called the Iron Confederacy (Nehiyaw-Pwat). The Iron Confederacy gradually expanded westward from the Hudson Bay Lowlands and Canadian Shield, to the Northern Great Plains, eventually waging wars against other Plains peoples – such as the Blackfoot, Ktunaxa, Shoshone, Hidatsa, Lakota, and Gros Ventre – to protect and expand their lucrative commercial success. Between the 1670s and 1780s, the Iron Confederacy utilized their exclusive access to European trade goods – such as firearms, iron knives and hatchets, coarse woollen cloth, wool blankets, cooking utensils, beads, and needles – to enhance their role in the fur trade economy and to become one of the most materially wealthy Indigenous peoples in Western North America.

Nakota (Assiniboine)Traditional Territory, Native-Land.ca

Although the fur trade did shift some economic conditions and altered some of the everyday aspects of the Nakota lifestyle, it did not fundamentally undermine or alter their culture, beliefs, and traditions. The introduction of horses during the second half of the eighteenth century brought the Nakota out of the Woodlands and Aspen Parkland onto the Northern Great Plains of Saskatchewan and Alberta, fully integrating themselves into the Plains Indigenous horse-raiding culture. The Nakota's acquisition of horses and exclusive access to muskets and iron weapons allowed them to launch a two-pronged western migration that brought them through the northern woodlands to the Rocky Mountains and in a southwesterly direction to the Great Plains. The Nakota's new wealth as traders, successful horsemen, and respected warriors reached a peak from the 1780s to the early 1800s. However, the westward movement of the Nakota also reflected some pressure from the Oceti Sakowin, who, gaining access to firearms from French, British, and American traders, began an aggressive push northward, fighting against the Iron Confederacy.

Because of the intensive economic competition between the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North-West Company, whose fur trade rivalry and aggressive inland expansion into Blackfoot and Gros Ventre territory (eventually spilling over into the Mackenzie drainage basin and the Columbia Plateau) the Nakota were soon cut off from their former lucrative position as middlemen in both the horse and fur trade. A smallpox epidemic in 1781-82 wiped out between one-third and one-half of the Nakota population. In 1837-38, just as the Nakota population was rebounding, another smallpox epidemic wiped out two-thirds of the Nakota. From an estimated population of more than 10,000 in the late eighteenth century, their numbers declined catastrophically to approximately 2,600 by 1890. Crow, Blackfoot, Gros Ventre, Hidatsa, and Lakota took advantage of the Nakota demographic crises and drove them further southward away from the bison herds roaming between the South Saskatchewan and Missouri River. Dwindling numbers forced most of the Nakota to concentrate themselves around Fort Union, constructed by the American Fur Company in 1829 on the Upper Missouri River.

There was an increasing demand for buffalo hides, dried buffalo meat, and pemmican to supply the fur trade and growing industrial centers on the eastern seaboard, which placed great pressure on the remaining herds. The subsequent near extinction of the bison, the remaining Nakota people reluctantly submitted to signing treaties with the Canadian and United States governments, and to living on reserve lands in the 1870s and 1880s. The aftermath of treaties was not favourable for the Nakota, who suffered from poor living conditions, government-imposed starvation, restriction of mobility, deteriorating health, cultural genocide in residential schools, and government bans and restrictions on religious ceremonies (such as The Sun Dance) and political activity. Contemporary Nakota communities in Canada largely reside in Saskatchewan and Alberta – Carry the Kettle Nakota First Nation, Mosquito-Grizzly Bear's Head-Lean Man First Nation, The White Bear First Nation, The Ocean Man First Nation, The Pheasant’s Rump Nakota First Nation – and were signatories to Treaty 4 (1874) and Treaty 6 (1876) in Saskatchewan.

Photograph of Olive Gordon (daughter of Assiniboine Chief Dan Kennedy of Carry the Kettle Band) in a doe-skin dress, with child. 1940-1969. S-B351. Saskatchewan Archives Board Photo Collection. Saskatchewan Archives Board. Our Legacy.

Resources:

- Nakota (Assiniboine) - Indigenous Saskatchewan Encyclopedia | University of Saskatchewan (usask.ca)

- Assiniboine Elders Workshop by Donald Medicine Rope (3) | Gladue Rights Research Database (usask.ca)

- Peace Treaty Between the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) and the Nehiyaw (Cree): Assiniboine Alliance | Gladue Rights Research Database (usask.ca)

- Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life | Gladue Rights Research Database (usask.ca)

- Arthur J. Ray, Indians in the Fur Trade: Their Role as Hunters, Trappers and Middlemen in the Lands Southwest of Hudson Bay 1660-1870. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974.