The Following is a selected summary from Hadley Friedland's "Accessing Justice and Reconciliation: Cree Legal Summary" Cree Legal Traditions Report

The full report "Accessing Justice and Reconciliation: Cree Legal Traditions Report" is available to read here

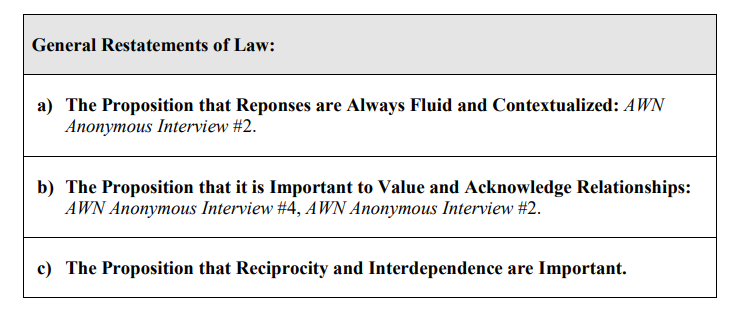

- The Proposition that Responses are Always Fluid and Contextualized

-

There is no static formula for how to respond to harms or conflicts under the Cree legal tradition. It is a fluid and deliberative process that is dependent on the circumstances posed by the harm or conflict, as well as the people involved. In almost every story and interview, the importance of flexibility and responsiveness to the needs and abilities of the people involved and available, and the context when responding to or resolving harms or conflict is evident. As one elder explained succinctly, because “each case will be different”, her responses to each one will vary as well.

While this explanation suggests some similarity to the fact-specific, case-by-case approach in the common law legal tradition, characterized by the Canadian model of law, the decentralized, non-hierarchical nature of the Cree legal tradition means that flexibility and responsiveness extends beyond what is typical in the common law approach. Although legal responses and resolutions reflect an individualized and contextualized approach, in the Cree tradition, the particular needs of the people involved, their relationships, and the situation or context are additional considerations that influence a number of key questions. These questions include who might be the legitimate decisionmaker, what the role and authority of the decision-maker might be, who has the relevant knowledge and expertise to be consulted, and who should be involved in the deliberation to reach a legitimate and effective response. (pp. 44).

- The Proposition that it is Important to Value and Acknowledge Relationships

-

In almost every story and interview, the importance of recognizing and considering relationships is evident. In two interviews, this point was made explicitly. At a general, cosmological level, one community member explained his belief that the Cree legal tradition needs to be understood as existing fundamentally within larger relationships. He argues that even the term, “law”, can be a misleading term for Cree people, if they associate it only with the Canadian model of law, which assumes a Canadian-style judiciary. Instead, he explained his understanding that Cree law relies on “protocols” — the proper conduct for ceremony, hunting, address of others, life generally, or “everything”. Underlying the importance of protocols, on this view, is the foundational importance of relationship between individuals and Creator, other humans, the land, and “nature.” Protocols are simply ways of understanding that, in respect of these relationships, “there’s right ways of doing things and there’s wrong ways of doing things.” Everything is seen as related parts of one whole: “the language, the culture, and protocols are all so intertwined, I think if you were to take one out, it automatically starts disintegrating the other ones.” He sees this as equally true for spirituality:

in the English language like we say spirituality, but in native cultures, I don’t think it was seen that way. I think it was life. It was all inclusive… And it’s, like, life with the medicines, like there’s life with spiritual realms. There’s life with people, like, but it’s all centred around relationships, right?

This worldview, with its emphasis on relationships and the interconnection of all aspects of life, is reflected throughout the stories and interviews. In particular, spirituality is not separated or elevated beyond other life realms. For example, elders talk matter-of-factly about recognizing warning signs through the observations of people’s behaviour and animals and the natural world, and through spiritual means, such as visions or dreams. Similarly, relevant knowledge and expertise for responding effectively to harms or resolving conflicts can be gained and recognized through these various means. The response principle of healing is most often discussed as implemented through spiritual means. Natural and spiritual consequences are both referred to as well. In general, relationships, between actions and consequences, between people and peoples, and between humans and the rest of the world, are assumed and permeate legal decision-making at many levels. At a practical level, another interviewee stressed the point that in small, tightly-knit Cree communities, it is vital to keep in mind that people who cause harm are not faceless, nameless agents of harm, but rather loved ones within families. One interviewer believed that, from the published materials he read, someone who had ‘turned wetiko’ was generally killed. When he asked about this, the elder responded quite emphatically: “probably someone who didn’t know nothing and had no compassion would just go kill somebody else.” The elder stressed that the appropriate response was to try to help the person instead, explaining: “these are our family members”.

This response suggests that Cree legal tradition does not operate in a way that artificially extracts individuals from community or ignores the reality that all people involved in a situation of harm or conflict exist within a rich network of familial relationships. Rather, these relationships are acknowledged and even accessed as resources. For example, a family member or elder that has a particular connection or is particularly respected by an individual will be asked to take on a persuasive role in resolving a conflict, or a supervisory role in temporarily separating someone who is dangerous from others, until he or she can be healed. The acknowledgement and valuing of relationships explains the strong rationale behind healing as the most important response, the importance of re-integration, ongoing observation and supervision, and also why avoidance is a response when the original issue is not seen as being as harmful as escalating a conflict within a community. (pp. 45-46).

- The Proposition that Reciprocity and Interdependence are Important

-

In many stories and interviews, there appears to be an unspoken assumption of reciprocity or an emphasis on the importance of reciprocity in all relationships. On a cosmological level, the acceptance that there are natural and spiritual consequences to every action informs peoples’ decision making and their responses to situations of harm and conflict. On a practical level, the principle of reciprocity is best illustrated through the obligation of a person to help others when capable and ask for help when incapable or vulnerable, the obligation to give back when asking for or receiving help, and the right to receive help when incapable or vulnerable. One inference supporting these rights and obligations could be that a person may never know when and how they may require help. Thus, reciprocity encourages people to value interdependence, rather than privileging an ideal of independence. (pp. 46)