The process of treaty-making changed between first contact and the present in ways that shed light on Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples. Early treaties were essentially commercial contracts. Today, recently negotiated (or renegotiated) treaties have become complex legal documents. Early treaties can be seen as compacts that were forged on Indigenous terms within the parameters of kinship systems and social responsibility. Evidence suggests that these early agreements generally worked for the mutual benefit of both parties. As the balance of power and economic interests shifted (largely due to the devastating impact of disease epidemics), treaty-making became less equal, less honest, and very much on the terms of European/Canadian settlers. The low mark for fair and mutually beneficial treaty-making follows confederation. By the late 19th century, First Nations had come to be seen by the new powers in Ottawa as an impediment to economic development and growth – as a problem in need of solving. The language of “covenant” used by Canadian negotiators to describe the numbered treaties signed at this time belies the disingenuous intentions of the Canadian government who were keen to take advantage of First Nations peoples’ vulnerabilities following recent epidemics and the decline of the bison. The discrepancies between what was stated orally and what was written in the official document, and the almost immediate failure of the government to live up to the responsibilities spelled out in writing, give strong evidence that the negotiations by the government were not sincere.

Despite the dismal record of the Canadian government in regard to the numbered treaties a shift in attitude by Canadians towards these treaties has been taking place and, recently, treaties have re-emerged as a tool for negotiating relationships with First Nations. Despite their long and storied history treaties remain central to the relationships between Indigenous people and the government of Canada as they are believed by a growing number of people to provide common ground necessary for a coming together of settler and Indigenous people around mutual interests.

Prior to contact, confederacies formed an important mechanism for organizing and regulating interaction (trade, ceremonial, territorial) between different groups based on kinship. Post contact, ‘fictive kinship’ assisted in the adoption of European peoples through accepted protocol, early seventeenth century to late nineteenth century. These rituals of trade and kinship contributed to and supported commercial compacts with the Dutch, French and British. Since commerce was the motivator for mutual agreements, treaties were informal due to European expansion objectives motivated by commercial as opposed to territory acquisition. The Royal Proclamation, 1763 is regarded as reserving land encompassed within its boundaries for the British Crown to the exclusion of other European nations, as well as recognizing Aboriginal title to territory and for outlining the land surrender process.

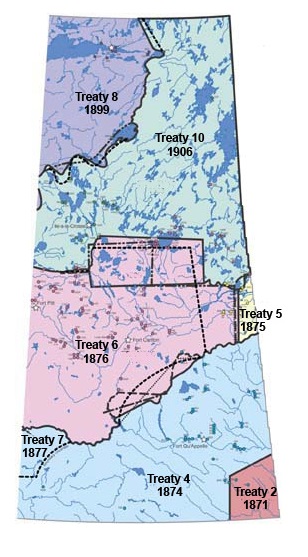

The 1850 Robinson-Huron treaties introduced large tracts of land in exchange for small parcels of land reserved for Indian settlement. Treaties negotiated between 1899 (Treaty 8) and 1921 (Treaty 11) were motivated by Canada’s interest in securing access to regions that held economic potential for Canada. 1973’s SCC rulings and self-government agreements (James Bay-Northern Quebec) as well as patriation of the Constitution and constitutional recognition of existing treaty and Aboriginal rights in 1985 shifted economic interests to legal protection. By 1973 an estimated five hundred compacts, covenants, treaties and agreements between Indigenous nations and the Crown had been entered into. Seven ‘numbered’ treaties blanket the province of Saskatchewan (Treaty 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 10) Treaty and provincial boundaries are incongruent, resulting in different interpretations related to jurisdiction. This is especially problematic for First Nations when treaty benefits (provisions) related to justice, health, and education are considered. The federal-provincial administrative jurisdictional wrangling has led to gaps in the provision of health services (Jordan’s Principle is an example) which further complicates current reconciliation efforts. Recent scholarship has veered away from the legal and policy-based interpretations of treaty to one that places responsibility on settler Canadians, based on the tenet that "we are all treaty people."

For Information on Numbered Treaties please see:

-

Treaty Research Reports | Gladue Rights Research Database (usask.ca)

-

Violations of the Spirit of Treaties | Circles for Reconciliation

Suggested Readings:

-

Arthur J. Ray, Jim Miller and Frank Tough. Bounty and Benevolence: A History of Saskatchewan Treaties (Montreal: Queen’s University Press, 2000).

-

Michael Asch. On Being Here to Stay: Treaties and Aboriginal Rights in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014).

-

J.R. Miller, Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-Making in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009).

-

Bill Waiser. Saskatchewan: A New History (Calgary: Fifth House, 2005).