Sixties Scoop and Child Apprehension

Up until the 1950s, there were discrepanices between federal and provincial responsibility for First Nations health and family services. This jurisdictional grey-area led to conflicts over which governing body was responsible for the provision of these services to First Nations youth and families. The Federal and Provincial governments decided that the responsiblity over health and family welfare fell to the provinces.

"The process began in 1951, when amendments to the Indian Act gave the provinces jurisdiction over Indigenous child welfare (Section 88) where none existed federally...With no additional financial resources, provincial agencies in 1951 inherited a litany of issues surrounding children and child welfare in Indigenous communities. With many communities under-serviced, under-resourced and under the control of the Indian Act, provincial child welfare agencies chose to remove children from their homes rather than provide community resources and supports." Sinclair, Niigaanwewidam James, and Sharon Dainard. "Sixties Scoop." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. November 13, 2020.

It was through the provincial child welfare agencies that Indigenous youth were apprehended and placed into non-Indigenous families and child welfare programs. The Federal Government claimed no fiduciary obligation or responsibility to Métis families and children, and thus the provincies were responsible. The apprehension of Indigenous children and youth from their families and communities came to be known as the “Sixties Scoop.” Indigenous children were stolen from their families and communities, and adopted into predominantly white, middle-class families. Despite its name, "Scooping" Indigenous children from their families and communities was not isolated to the 1960s; the practices continued both before and after the 1960s, some of these practices continue today. This is demonstrated in the disproportionately high rates of Indigenous children caught within the Child Welfare System.

"It is well-known that Indigenous children are over-represented in both the child protection and justice systems in Saskatchewan and across Canada. Year after year, the deaths and injuries we review are a stark reminder of this dark reality. In 2021, 22 of the 24 deaths (92%) and 23 of the 29 critical injuries/incidents (79%) that came to our attention involved Indigenous children and youth." (Saskatchewan Advocate for Children and Youth, 2021 Annual Report, 34).

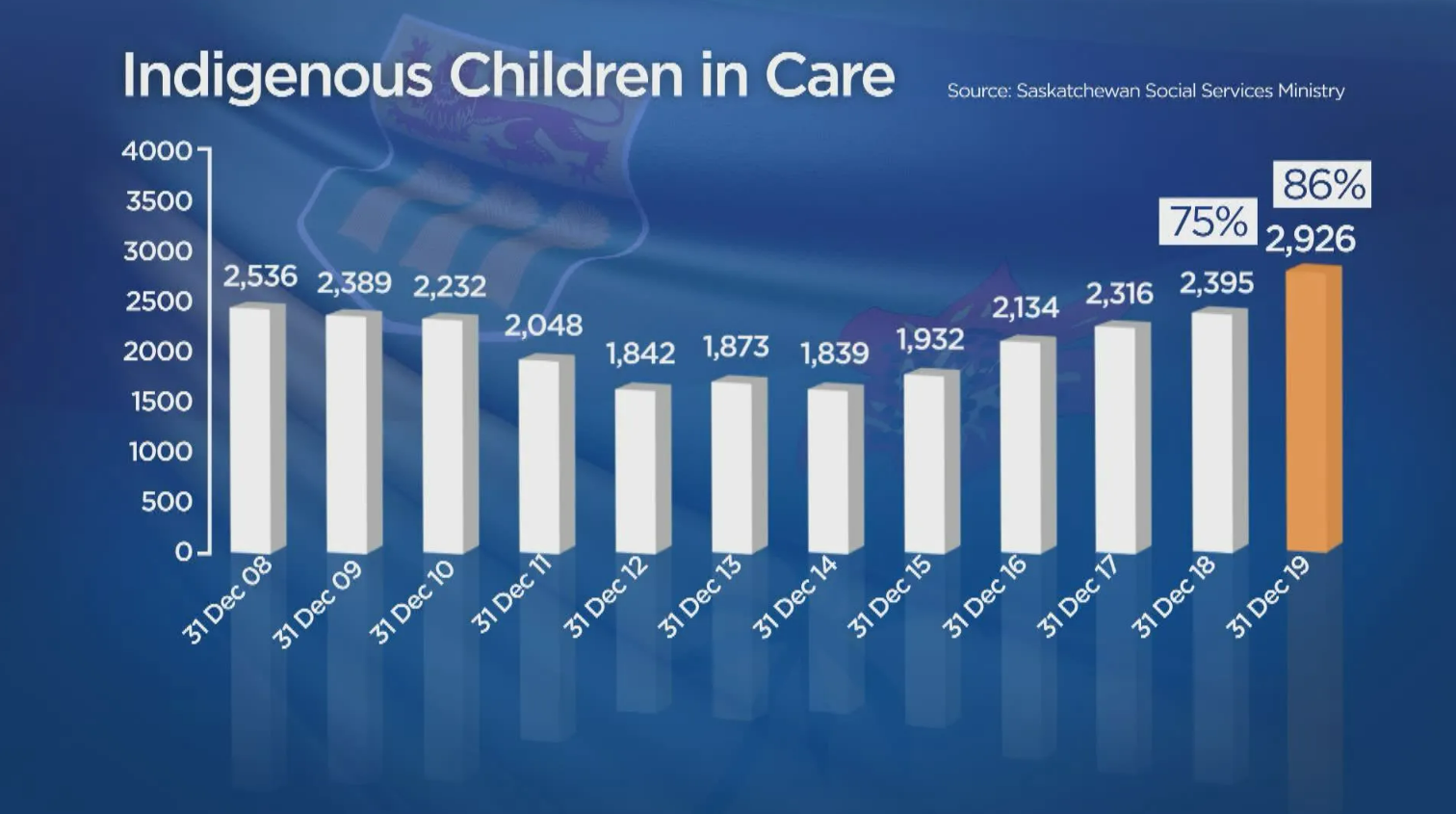

As of 2019, Saskatchewan Social Services Ministry reported that 86% of children in care are Indigenous (Global News). Statistics Canada reported that in 2016, Indigenous peoples represented 16.3% of Saskatchewan's total population (Statistics Canada, Focus on Geography Series, 2016).

The Sixties Scoop experience left many adoptees with a lost sense of cultural identity. The physical and emotional separation from their birth families continues to affect adult adoptees and Indigenous communities to this day.

In Saskatchewan, particularly the Northern region, Indigenous children were taken or ‘scooped’ from their communities and generally relocated to white families in colonial settlements. Under the administration of the provincial CCF (the pre-cursor to the NDP), scooping children from the North was deemed necessary because Northern foster care was reportedly unable to meet capacity. But of course, scooping Indigenous children from their home communities fostered a social and cultural disconnect that aligned with Canada's ultimate goal of assimliation and cultural homogeny. Scooping children contributed to assimilation by disconnecting Indigenous youth from their ancestral lands, families, communities, resources, and livelihoods. Many Indigenous children who were scooped at birth or an early age were not told of their relocation or Indigenous kinship by their adoptive guardians, and only found out later in life.

"The department of Indigenous Affairs indicates that the number of Indigenous children adopted between 1960 and 1990 was 11,132. However, more recent research suggests upwards of more than 20,000 First Nation, Métis and Inuit children were removed from their homes. Many children were also sent abroad, some as far away as New Zealand. Depending on the source, in 1981 alone, 45 to 55 per cent of children were adopted by American families." Sinclair, Niigaanwewidam James, and Sharon Dainard. "Sixties Scoop." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. November 13, 2020.

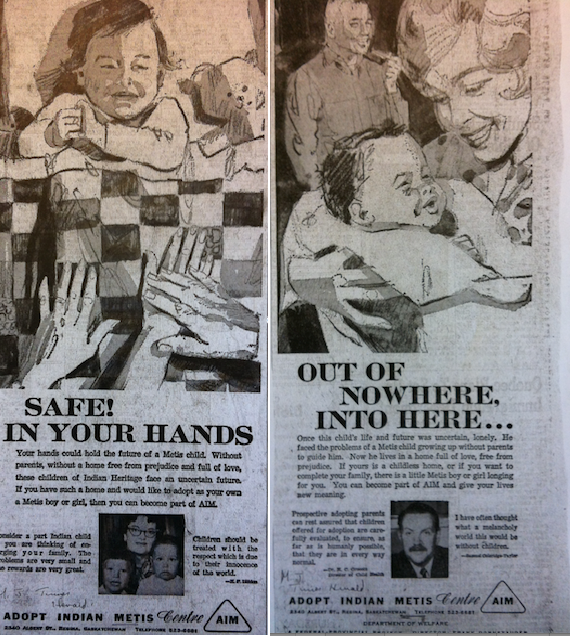

Newspaper advertisements for the Adopt Indian and Métis Program, late 1960s, Saskatchewan.

"The long-lasting effects of the Sixties Scoop on adult adoptees are considerable, ranging from a loss of cultural identity to low self-esteem and feelings of shame, loneliness and confusion. Since birth records could not be opened unless both the child and parent consented, many adoptees learned about their true heritage late in life, causing frustration and emotional distress. While some adoptees were placed in homes with loving and supportive people, they could not provide culturally specific education and experiences essential to the creation of healthy, Indigenous identities. Some adoptees also reported sexual, physical and other abuse. These varied experiences and feelings led to long-term challenges with the health and livelihood of the adoptees. As a result, beginning in the 1990s, class action lawsuits against provincial governments have been pursued in Ontario, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, and are still before the courts." Sinclair, Niigaanwewidam James, and Sharon Dainard. "Sixties Scoop." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. November 13, 2020.

Indigenous parents and their children continue to report ‘scooping’ through child welfare services with further placement into the foster system. For example, scooping through the practice of Birth Alerts wherein hospital staff alerts child welfare services if they deem the child ‘at risk’ from their parents. Parents are not informed of the action nor provide consent. Birth Alerts have historically and contemporarily targeted Indigenous mothers, inaccurate and unfair characterizations have included being unfit, or disengaged from their child. Birth Alerts have allowed hospitals authority over who is deemed ‘fit’ to parent a child, and these decisions are often informed by systemic racism, classist assumptions, and racial stereotypes.

See Also:

- Adopt Indian and Métis Program

- Intimate Integration: A Study of Transracial Adoption in Saskatchewan, 1944-1984