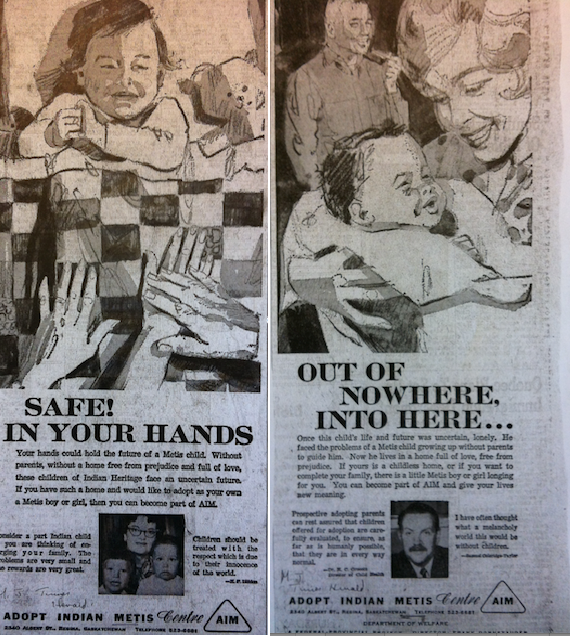

This essay provides a brief analytical introduction to the impact of colonialism in terms of undermining social determinants of health, thereby contributing to the proliferation of disease epidemics on the Prairies (please see "additional notes" below for bibliography): From 1492 onwards, disease epidemics resulted in Indigenous mortality rates ranging in upwards of eighty five to ninety five percent, causing tremendous suffering and wreaking devastation on the social and political organization of Indigenous nations (Daschuk 2013, 12; Kelton 2007, 37; Sundstrom 1997, 306). Although North America was not completely disease-free prior to Contact, European trade exchanges and practices of colonization introduced sociocultural change and heightened vulnerability to deadly pathogenic infections (Daschuk 2013, 1-2). Currently, the most widely accepted explanation of disease-emergent mortality rates within the disciplines of history, anthropology and archaeology is virgin soil epidemic theory (VSE) (Jones 2009, 197). First argued by Alfred Crosby in The William and Mary Quarterly in 1976, Crosby posits that much like the “virgin soil” of the largely agriculturally uncultivated Americas in 1492, Indigenous populations were inexperienced with the contagious bacteria that Europeans carried (Kelton 2007, 1). This theory, therefore, is used to explain the severity of Indigenous mortality rates as having derived from a lack of developed immunity due to a population’s first exposure to infection or because all members of the community who had been exposed to the disease have died (Daschuk 2013, 11-12).--- Crosby’s focus on biology is problematic, however, in its invisibilization of factors like nutrition, methods of subsistence, migration patterns and trade practices, thus ignoring the impacts of colonialism and capitalism in terms of altering these variables through land invasion and dispossession as well as sociopolitical disruption of Indigenous nations (Kelm 1998, 55; Kelton 2007, 1). To illustrate, as it relates to Saskatchewan, archaeological evidence dating to the 1670s reveals that the fur trade had already begun to shape the Northern Great Plains region, and that less than one hundred years later, the introduction of commercial hunting practices had resulted in a shortage of fur-bearing animals along the North Saskatchewan river, as reported by HBC employees (Daschuk 2013, 11). Although Europeans perceived Indigenous diets to be a cause of disease, in truth, the high-protein and nutrient-rich diets of Indigenous peoples had provided them with relatively stable health for millennia, particularly in comparison to their European counterparts. The erosion of these diets, therefore, in addition to the introduction of European nutrient-poor foods such as flour and sugar, increasingly contributed to their susceptibility to disease, particularly after the near-extinction of the buffalo in 1870 (Kelm 1998, 36; Kelton 2007, 2; Daschuk 2013, 10).--- The VSE theory also neglects to acknowledge the motives of colonial actors in terms of acquisition of land and wealth, thus exercising detachment from the moral sphere and reinforcing western imperialism by affirming the superiority of positivism and rejection of metaphysical discussions of morality. In fact, Daschuk writes “the spread of foreign diseases among highly susceptible populations comprised a tragic, unforeseen, but largely organic change. Those who place human agency and greed and the expansionism of colonial powers at the centre of the decline of indigenous nations in the western hemisphere are missing half of the story; the role played by biology cannot be ignored” (pages xv-xvi). And yet, Daschuk uses the majority of his book to argue the predominant role of pathogenic factors in Indigenous rates of mortality. While there is validity to VSE as it relates to the role of a lack of immunological defences, as a philosophical perspective, positivism is highlighted by Indigenous scholars like Linda Tuhiwai Smith as being closely interconnected to imperialism and one means through which colonizing nations assert their superiority over Indigenous peoples. By choosing to perceive disease epidemics primarily in impersonal and positivistic terms, VSE perpetuates the western imperialist scientific detachment of European medicine (Kelm 1998, xvi-xviii; Smith 2012, 92-116; Daschuk 2013, xvi).--- Aside from these flaws, it is ahistorical and anachronistic to impose a biological model such as VSE on non-Indigenous understandings of the severity of disease epidemics on Indigenous people. This applies both before, during and after the period of 1870-1906, an important transitional time frame for the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Saskatchewan marked by the near-extinction of the buffalo, the numbered treaty era, the establishment of the settler state, the introduction of residential schools (framed as “Indian education” within the Indian Act) and the beginning of significant settler encroachment. The era of 1870-1906 is also marked by the introduction of medical care to Indigenous peoples. Yet, the provision of medical access was delayed in comparison to that offered to non-Indigenous peoples, resulting from colonial attitudes in which Indigenous people were largely blamed for their own pathologies. That is, there existed a prevailing belief that the supposed cultural backwardness of Indigenous people, when combined with their physical weakness, were determinants that encouraged sickness and would eventually lead to their extinction (Daschuk 2013, x; Kelm 1998, xvi & 101-6). The widespread acceptance by non-Indigenous interlopers of the gradual and unavoidable disappearance of Indigenous nations had generated a broadly-accepted belief in the futility of offering medical aid (Jones 2004, 139; Kelm 1998, xv-xvii & 100). Disease epidemics were therefore seen as a natural result of this ethnic inferiority, after which non-Indigenous colonial actors would exploit the losses of Indigenous people by apprehending newly depopulated territories and assets (Lux 2001, 13; Jones 2004, 2-3).--- For example, although written records indicate the occasional speculation of colonists regarding the role of Europeans in contributing to the deaths of Indigenous populations, for the most part, health disparity rationalization explicitly reinforced ethnic hierarchies through portrayals of Indigenous peoples as possessing enhanced genetic susceptibility to the contraction of diseases. Other common rationalizations include victim-blaming references to uncivilized behaviors and/or detrimental individual choice - reflecting a tendency of Euro-Canadians to moralize and pathologize Indigenous people and their actions. To illustrate, one example of the Crown’s assimilatory logic is that it was the laziness or “indolence” of agriculturally-averse, migratory Indigenous peoples that led to poverty and slovenliness, and in turn, disease. To discipline a perceived tendency towards “work-avoidance”, the government exercised tight economic control over reserves, including minimal food rations. On many reserves, the government broke treaty promises to provide aid, farming implements and livestock - resources that would have prevented malnourishment, illness and death. Before and after the creation of the Canadian state, however, the states of physical and psychological stress caused by intense malnutrition and starvation, geographical displacement, crowded reserve living conditions, the questioning of spiritual beliefs and the loss of community leaders, Elders and family members all enhanced vulnerability to disease and diminished chances of recovery (Lux 2001, 4 & 20-59; Jones 2003).--- Historic and contemporary explanations of disease pathologies are not transformed into neutral or objective facts by virtue of the use of scientific rhetoric. Rather, philosophical biases and racial ideologies of authors are revealed in the utility of the health disparity theories in question, particularly in relationship to preserving or dismantling the social, economic and political privileges and advantages accorded to non-Indigenous people within colonial states (Jones 2004, 3 & 7; Lux 2001, 13). As previously discussed, explanations such as those used by the government to justify assimilation fail to de-centre the inevitability or justifiability of colonialism, and neglect the impact of colonial and capitalistic systems on Indigenous lifeways, including the means through which personal autonomy and choice were constrained through the sociocultural breakdown of Indigenous nations, and later, through policies of assimilation (Jones 2003, 3 & 41-3 & 83 & 134-5 & 223-4; Kelm 1998, 39; Lux 2001, 151).