The following essay provides a brief introduction on the effects caused by housing insecurity and poor quality housing, with attention paid to the disproportionate impacts for Indigenous peoples (see bibliography below):

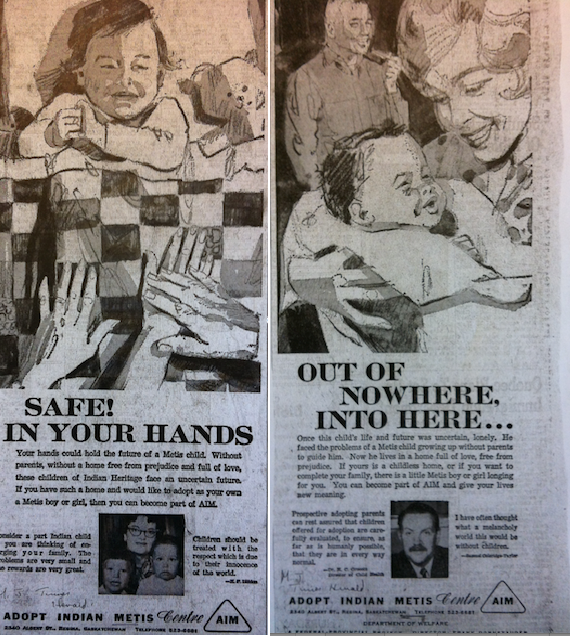

The result of one hundred and fifty years of colonial government oppression has been the large number of Indigenous peoples (First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) who live in poverty at levels below the LICO (Low Income Cut-Off). Indigenous peoples have been systematically disadvantaged by frequently being given the least productive reserves and farmland, being hindered by the pass system from selling the products of their labour, to work away from reserves for extended periods of time without losing their status, road allowances which kept Métis people impoverished, and the denial of economic and political self-determination due to paternalistic government policies. The cumulative effects of these and other assimilative government policies has been barriers to socioeconomic instability including unemployment, inaccessibility to education, poor health outcomes, addictions, and lateral violence.

Inaccessibility to affordable housing is fundamental to understanding these disparities, and creating access is imperative to establishing equity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples alike. Limited access to safe housing is something that affects multiple and frequently overlapping populations: immigrants, people with disabilities, working class people, Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour, people with addictions, people who have criminal records, youth who do not live with a parent/guardian, the elderly, queer and transgender people, single parents, and of course, people who are unhoused. In their pre-budget submission to the Department of Finance in 2003, the Assembly of First Nations noted, “The lack of quality housing contributes to social problems such as child poverty, suicide, low educational attainment, alcoholism, and family breakdowns” (Barnsley 2003).

Incidentally, aforementioned factors of poverty, unemployment, educational inaccessibility, lateral violence, and addictions are frequent experiences of those caught within the Canadian criminal justice system. This underscores the necessity for adequate and affordable housing for Indigenous peoples, and others who are prevented from it due to the value placed on ‘whiteness’ or lack thereof (“Aboriginal Housing Needs in Saskatoon: A Survey of SaskNative Rentals Clients” 2004, 2; La Prairie and Stenning 2003, 187).

Indigenous peoples in comparison to white settlers, statistically, are significantly more likely to experience trauma due to systemic factors such as the experience of racial discrimination in employment, education, policing, and acquisition of services/resources. Often, Indigenous peoples experience racial discrimination causing barriers to resources and services; this not only has immediate effects on a person’s state of wellbeing but may prevent them from accessing support in the future due to fear the discrimination will happen again. Example, an Indigenous single mother applies for a house rental, but she is denied during a viewing and the property owner is racist towards her. Going forward, the fear and anticipation that something will happen could prevent her from reaching out to support services, going places, applying for housing, etc.

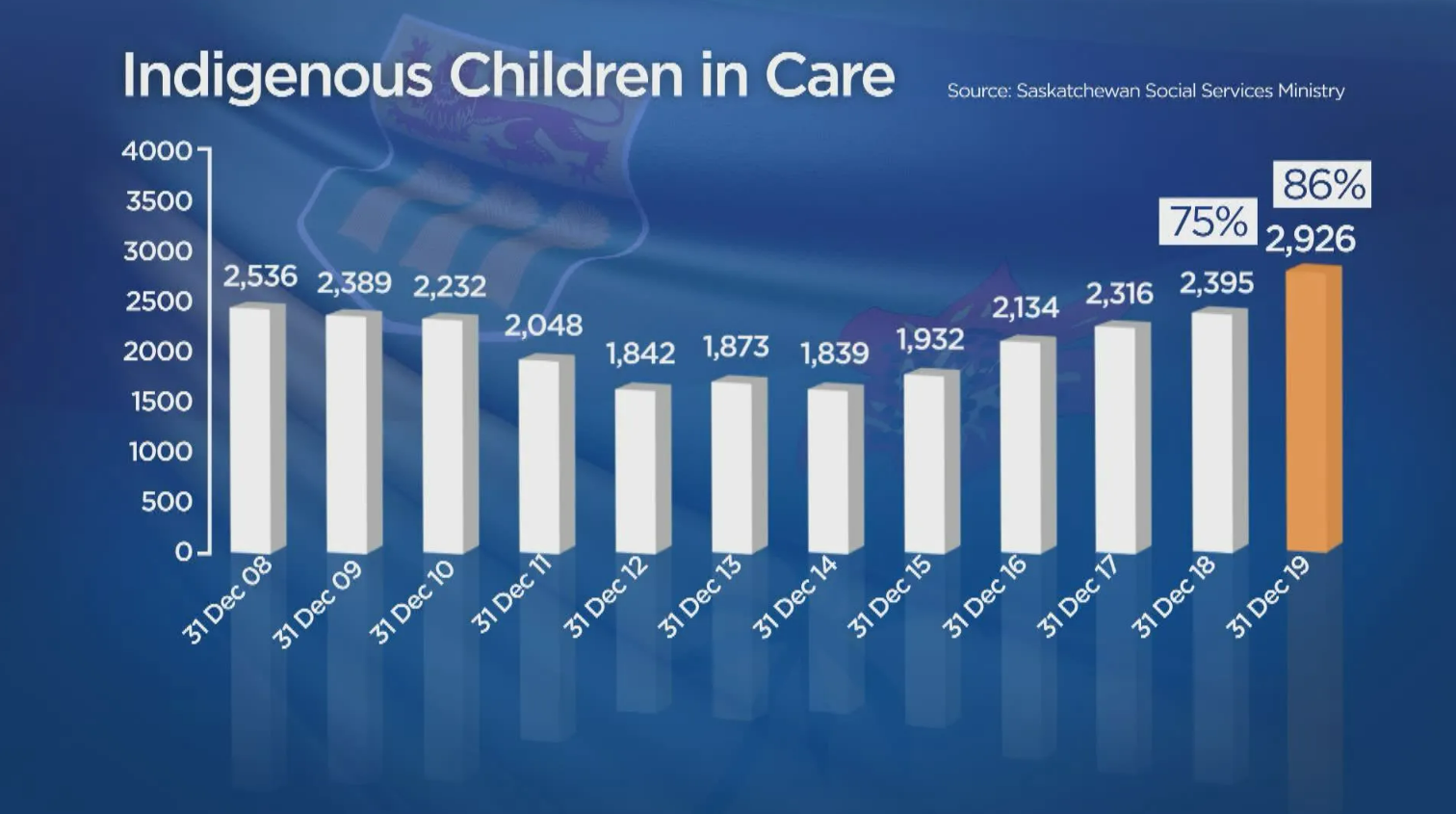

For Indigenous persons trying to get out of poverty, they may experience a lack of financial resources or assistance in urban and rural areas, accompanied by increased policing in Indigenous communities (e.g.: the neighbourhoods of Riversdale and Pleasant Hill in Saskatoon have higher police surveillance than Evergreen or Avalon; according to former Judge Harold Johnson, northern Indigenous communities experience a high presence of RCMP surveillance). One example is existing provincial programs such as Social Housing, which have long waiting lists and are insufficiently equipped to accommodate the number of people in need. According to Campaign 2020, “For children in First Nations families, the poverty rate in 2016 was 49.4 per cent. Among those families indicating they were Métis, 28.4 percent were in low-income households.” (Campaign 2000, Saskatchewan Child and Family Poverty Report, 2020). As of 2021, over one quarter or 26.1% percent of children within Saskatchewan live under the poverty line, the highest representation of these come from single-mother households (Global News, https://globalnews.ca/news/7722857/saskatchewan-children-poverty-report/, 2021).

Individuals living in poverty who are able to find housing may be limited to options that are overcrowded, or in poor repair. Young members of these groups may not have a sufficient number of safe spaces to spend their time, as community organizations and safe spaces that do not require money have limited funding, staff, and operating hours (e.g.: libraries, community halls and centres, EGADZ, shelters, The Lighthouse). For many of these community organizations, sobriety is mandatory for admittance creating another barrier to safe spaces for youth and adults. These difficulties can combine to create an overall sense of stress and frustration in surviving within urban surroundings, and in struggling to financially survive. The lack of support and resources can contribute to criminal justice system contact / re-contact. That is to say, the cumulative effects of settler colonialism and the ongoing dispossession of Indigenous lands resulting in impoverished conditions leads to a higher rate of Indigenous peoples in contact with the criminal justice system. (“Saskatoon Aboriginal Neighbourhood Survey: A Survey of Aboriginal Households in City Neighbourhoods” 2004, 12; Newhouse 2003, 245; Trevethan 2003, 195).